Learning Landscapes: Learning to Look

Mood: Curiously Inspired | Post Type: Work Spotlight | Weeks Until Show: 35

From Instinct to Intention

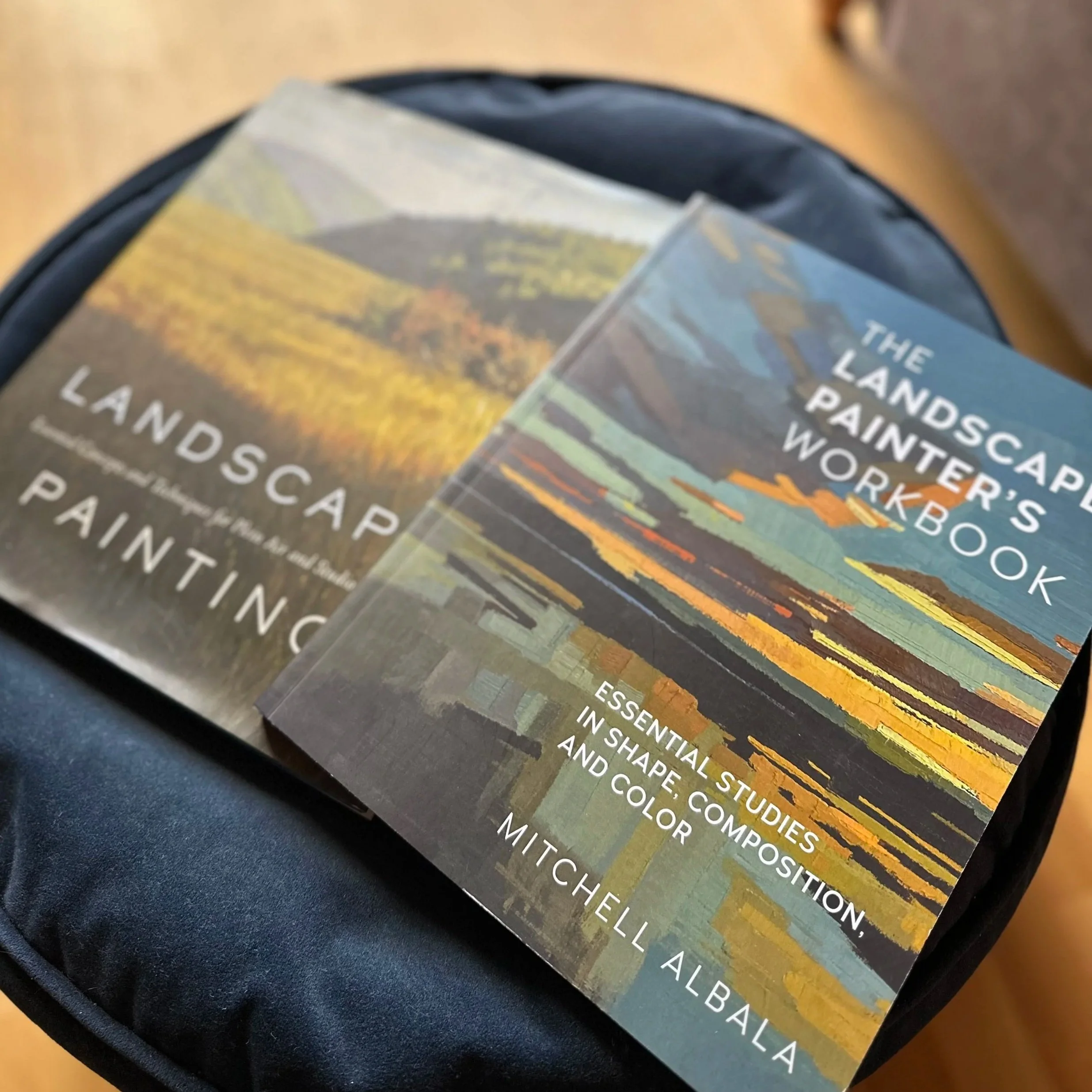

The more I’ve progressed toward creating larger landscapes, I’ve felt a growing need to understand what actually makes an image work—how balance, structure, and the movement of the eye all come together. My starting point was books. I have two in particular that have become crucial building blocks in my learning.

At first, it was simple curiosity—how should a landscape be constructed? But that curiosity has gradually turned into a full-blown obsession.

As you may know, I spend a lot of time listening to creative podcasts during my many motorway journeys. Recently, I heard two separate interviewees say something that really stuck with me: their art degrees didn’t teach them a huge amount about how to create art, but instead taught them how to look at art. That really resonated with me, but in the opposite way. I’ve always relied on instinct and gut feeling when responding to art, rather than consciously examining the many different facets that make it work—or sometimes, why it doesn’t.

Now, I’m finding myself slowing down, looking more carefully, and asking better questions. It feels like I’m learning to see landscapes not just as finished images, but as a series of thoughtful decisions, each one shaping the whole.

Beyond the Rule of Thirds

My photography degree didn’t teach me a huge amount of technical skill. My main compositional rule was the rule of thirds, and it carried me through most of the images I created. At the time, my work was largely people-based—underwater photography featuring water nymphs and fairies, alongside reportage wedding photography. That, however, feels like a whole different story, and a lifetime ago.

I often said, “I’m not a landscape photographer.” I thought it was a lack of patience—the idea of sitting for hours waiting for a single shot never appealed to me. But the more I reflect, the more I think it had less to do with patience and more to do with not truly understanding how to build a landscape beyond the rule of thirds.

Finding the Missing Piece

I mentioned earlier that two books have been crucial to my learning. They’re actually by the same author, and although I hadn’t picked them up in a while, I recently happened to hear him interviewed on the Learn to Paint Podcast—a new favourite of mine. Check out the excellent podcast by Kelly Anne Powers.

I know I’m not painting in a literal sense, but so much of what a painter has to consider before committing to canvas feels exactly the same. Composition, balance, structure, and intent all need to be resolved early.

In the interview, Mitchell Albala spoke about the importance of a Notan study. A Notan study is a simple value-based sketch, usually reduced to just light and dark shapes. It strips an image back to its most basic structure, allowing you to test balance, rhythm, and composition without getting distracted by detail. At its core, it’s about designing the underlying framework before anything else is added.

A few weeks back, I had almost abandoned my card deck idea—something I created to help guide me through the process of designing my pieces. The project had stalled, and once again I assumed it was because it had lost its shine (a familiar pattern for my ADHD brain). But my last blog did exactly what I’d hoped it would: it re-enthused me to carry on. I genuinely believe the card deck has legs.

After listening to Mitchell Albala’s interview, the penny finally dropped. A Notan study was the missing piece. It would provide the structure—the very foundation—that the card deck needed but hadn’t yet defined.

Often, when an image is finished and something still feels off, it’s the underlying structure or composition that’s at fault. At that stage, no amount of tweaking will make a difference. For me, working in glass, that truth feels even more final—once it’s solidified, there’s no going back.

Light-Dark Harmony

A traditional Notan study is built using just black and white. The term Notan comes from Japanese aesthetics and roughly translates to “light–dark harmony.” It’s about the balance and interaction between positive and negative shapes.

When the concept was later adopted into Western art education—particularly through design and painting—it became formalised as a black-and-white exercise. The restriction was intentional: by removing colour and mid-tones, the artist is forced to confront the underlying structure of an image. If a composition works in pure light and dark, it will almost always work when complexity is added later.

For me, though, I struggled. I still needed a hierarchy of shapes to properly understand what was happening, so I introduced a mid-value. And, as it turns out, this isn’t a betrayal of the Japanese tradition but an evolution of it.

It made a difference for me—and if something works, why make it harder for yourself?

The original image on the left was taken on a Dorset beach back in March and then tweaked using a phone app called Brushstrokes, which helped simplify the image—something my brain still finds difficult to do.

From there, I reduced the scene down to three values, simplifying the shapes even further to see what would happen. Where does the eye go? Which areas hold attention, and which ones fall away? Stripping it back like this made the underlying structure far more visible than I expected.

What’s really made the difference is buying Procreate, which I’m using on my dad’s iPad. My mum kindly gave it to me—it’s large and heavy, and she already has the smaller versions, so it was sitting unused.

There’s something quietly lovely about seeing his profile picture come up on the screen. I know he’d be chuffed that it’s being put to use, and he’d probably appreciate the card deck too. Although he wasn’t an artist (at least not that I know of), he was a classic engineer, and the process of how things work—how systems are built—would have been very much up his street. Procreate has given me the freedom to experiment quickly—adjusting shapes, shifting values, and immediately seeing how those changes affect the way the eye moves through the study.

That ability to test and rework ideas without commitment has been invaluable. Instead of guessing whether a compositional decision works, I can see it almost instantly, long before anything becomes fixed or irreversible.

The Notan study has now become Stage 2 of my card deck. From there, the next step is Composition, where structure and flow begin to take shape.

Until next time.

This is Episode 12 in my ‘Solo Show Diary’ series — a behind-the-scenes look at how my work develops. You can find my earlier posts here.